O’Brien’s words of wisdom

Here is a lovely piece of writing from the recent late Glenn O’Brien about Kid Creole and the Coconuts – enjoy!

October 1980

a pan-equatorial rhythm safari

AUGUST DARNELL by Glenn O’Brien

The Savannah Band released two great LPs on RCA Records: DOCTOR BUZZARD’S ORIGINAL “SAVANNAH” BAND and DOCTOR BUZZARD’S ORIGINAL SAVANNAH BAND MEETS KING PENNET; and recently, after a long vacation the band released DOCTOR BUZZARD’S ORIGINAL SAVANNAH BAND GOES TO WASHINGTON (on Elektra Records). During the Savannah Band’s vacation, August created his own band: KID CREOLE AND THE COCONUTS, and they have managed to do what the Savannah Band didn’t. They play a lot. Featuring August as The Kid Creole, The Coconuts debut album is out now on ANTILLES RECORDS.

August has also been a hit as a songwriter and a producer. He produced MACHINE’S debut album of the same name and wrote several of the songs including their hit single, THERE BUT FOR THE GRACE OF GOD GO I (Hologram Records). He contributed several great songs to THE AURAL EXCITER’S album, SPOOKS IN SPACE (Ze Records). Also for Ze he produced and wrote for the CRISTINA album—which contains his great song JUNGLE LOVE. August produced the debut album of former Savannah Band singer GICHY DAN, (on RCA Records). Another great collaboration was his snazzy remix of JAMES WHITE’s neo-classic CONTORT YOURSELF—one of the greatest moments in disco.

August may be a genius lyricist, disco’s COLE PORTER, and a great producer, but wait till you see him transform before your very eyes, stepping on the stage and becoming the Kid Creole. He has moves and uses them like a conductor, leading a panequatorial rhythm safari revue from city to jungle and back.

GLENN O’BRIEN: What’s your first musical memory?

AUGUST DARNELL: My first musical memory dates back to about 1957. It was a record my father was playing, Day-O, by Harry Belafonte. I was 7-years-old then and prior to that time I was very much into the written word. Hearing this record was really my first musical experience because there was something about it that transported me out of where I was to another place and time. It was in the Bronx that I heard this, by the way, so that’s why being transported to another time and place was very romantic. I fell in love with the idea that music could do that to someone.

GLENN: When did you start playing?

AUGUST: I became active only after my brother Stoney actually sat me down and taught me how to play bass. He was playing guitar and he wanted somebody to accompany him, so the practical thing to do was to teach his little brother—which is what he did. I was 11 or 12-years-old.

GLENN: What kind of records were you listening to then?

AUGUST: My early childhood was spent listening to a lot of Harry Belafonte. I started getting into the Island sound. Later, like every child of the time, I was heavily influenced by The Beatles, and the British invasion. Oddly enough, what The Beatles did to me was to stimulate my interest in Elvis Presley. To this day, Jailhouse Rock is one of my favorite songs of all time. The British invasion, because it was so wonderfully glorious, started my juices flowing, and once the juices started flowing, my curiosity started flowing, my curiosity led me to appreciate Elvis Presley, Motown, etc., etc… There was a lot of glory and romantic heroism involved with The Beatles. They came over here and to a young kid they seemed like crusaders. They brought a new sound. Sometimes you’re too close to the forest to see the trees, to appreciate the things in your own home town.

GLENN: What was your first band?

AUGUST: The first band was an outfit that Stoney organized way back. It was called The Strangers. Four cats, we used to dress in dark shades and we played clubs in the Bronx. After that I became involved in a band called The Air Bubbles. I broke away from Stoney because he was getting into some intricate stuff and he said he needed more experienced musicians. He didn’t throw me out. We understood. The Air Bubbles were just a local rock band. We played The World’s Fair in Flushing, one of the high points in my life.

GLENN: What kind of material did these bands do?

AUGUST: The Strangers were heavily influenced by The Beatles. Stoney always had a mind for re-arranging things. So he would take Beatle tunes and re-arrange them with jazz chords. It was a weird effect. He could never do a song the way it was—he loved to dib and dabble with the arrangements, especially distorting the harmonies. The Air Bubbles were just straight ahead Top 40, nothing original. And after The Air Bubbles there was a group called Unum Mundo—One World. That was another one of Stoney’s concoctions. And after Unum Mundo I went off to college. I wasn’t involved in any musical groups there. And I received the historic phone call from Stoney that he was putting together something he was going to call The Savannah Band and did I want to be aboard? And I asked him what “being aboard” meant. And he said it meant a lot of commitment, a lot of rehearsals, etc., etc. and he said he wanted me to do the lyrics for the songs. And I said, “Sure, why not?” But as time went on I got more and more involved in education.

GLENN: Where did you go to college?

AUGUST: Hofstra University. I was majoring in English and this was the time of the draft, and the draft was taking people left and right so I had to get real serious. I had to switch my major. I originally majored in drama, but I switched to English so the draft board would leave me alone. Because in those days there was a shortage of English teachers. So I became an English teacher. And that really turned Stoney off because it was a full-time job, limiting rehearsals and all. So I did about three and a half years of teaching until Stoney said that it could be only one way or the other: either you stay a teacher or you come aboard this full time. So I quit teaching and the rest is anti-history.

GLENN: Were you a popular teacher?

AUGUST: I was extremely popular. The kids loved me. I had the drama club after school that was my pride and joy. I was really existing for that drama club. We put on plays that I had written and they were a gas. In fact, I had many sessions in the principal’s office— me, the teacher—being chastised for representing a bad code of conduct and demonstrating bad ethics in the plays that I put on. He just couldn’t understand where they were coming from. But the kids loved it and in the end they ruled. They over-ruled his decision. They decided they must have Mister Browder’s plays—it was Mr.Browder in those days. And they rallied to his cause, and won over even though the teachers couldn’t understand what I was doing.

GLENN: What were the names of your plays?

AUGUST: One was called Escapism. It was about a black kid who was put on trial because he had no pride in his heritage. There were some strange things examined in that. There was another one called Neo-Cowboys in the Land of Jizz which was about two kids who staged a coup d’etat at their high school because they felt they could do a better job than the teachers. And you know the administration didn’t want to see that. They thought it was planting some bad attitudes in the kids’ brains. There’s another one called, Good Morning Mister Sunshine, which is a bit autobiographical. Interestingly enough, that was something that I further developed into a two act play that won me a CAPS grant in 1976. But that was the most interesting part of my teaching experience, meeting those kids. I believe to this day that they taught me more than I taught them. They had such a zeal for living.

GLENN: Have you written any plays since then?

AUGUST: Yeah, I’ve been working for two years on one that is a revision of ’NeoCowboys.’ I had a reading of it two years ago at Frank O’Hara’s so-called “Third World Workshop” up in Harlem that was very successful. And I’ve been working on a musical called Soraya—it’s an idea from the King Penett album that’s been in the hands of Joseph Papp for the last two years. He’s sold on the idea but he’s not happy with any of the revisions. It’s a bizarre play—a myth set in the Forties that deals with miscegenation on a remote island. Papp loves it but he hasn’t endorsed it yet because he can’t find a script that works. As a matter of fact, I collaborated with Ed Bullins on that play. Maybe that’s why he hasn’t endorsed it. But one day I’ll sit down and get the right edition. It’s a matter of time. The music is very tropical—island, reggae, calypso.

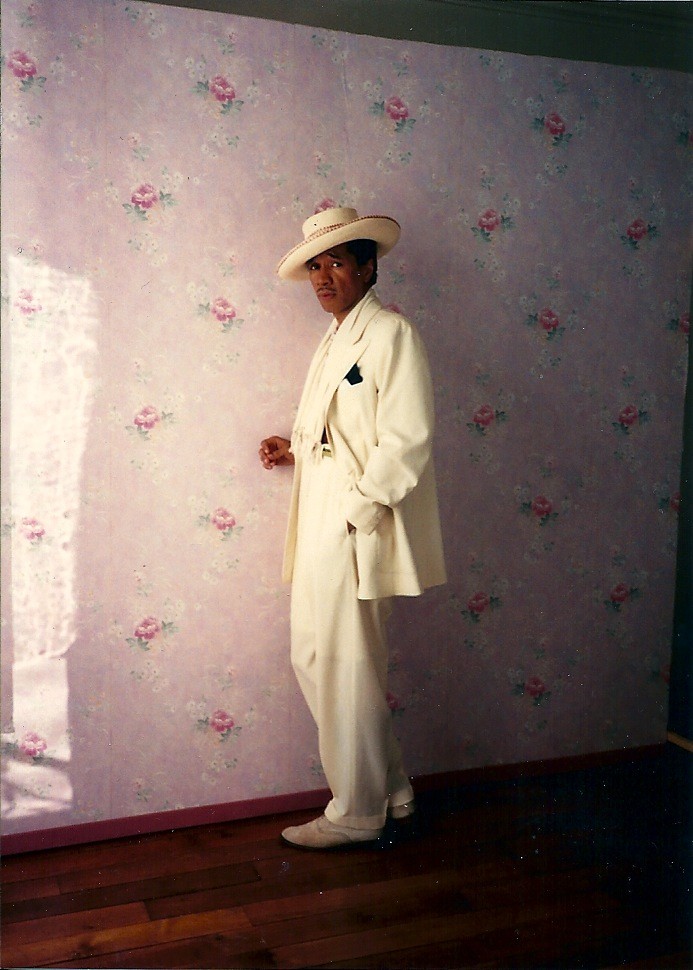

GLENN: When did you get into your present style of dress?

AUGUST: I’ve always worn three piece suits with large lapels. Primarily because I was such a student of the cinema. I was reared on the old movies and my idols were John Garfield, Bogart, Cagney and George Raft, and the females that accompanied them, Joan Crawford, Hedy Lamarr, Bette Davis and Ann Sheridan. The wonderful ladies. There was something about the people of that era that made me aspire toward their dress, and I could never quite get it. During my high school and college days I’d get the Pierre Cardin suits because they had nice lapels, but something was always wrong. And I couldn’t afford to have them tailor-made. I liked the suits but I’d look at the TV and I’d think, “Something is missing, what is it?” In 1974, I was visiting Stoney one day and he said, “I want to show you something” and he pulled out a pair of pants and said, “Try these on.” They were baggy, pleated gabardine pants. And I tried them on and the minute I put them on I said, “This is it!” The jackets had been okay. But there was always something wrong with the crotch of those designer pants. They were Europeanbased and Italian men like to display their genital forms. So Stoney had found the missing link. It was the crotch dropping almost to the knee. The looseness of the pants truly transformed me. I said, “This is John Garfield. This is it!” So he said, “This is it. This is the new code. This is what we are going to be about.” We started buying up all the suits we could. Now I couldn’t care what happens to fashion. I’m comfortable with what I’m wearing. I know it sounds odd to put this much weight on attire, but since the transformation’s occurred I’ve been so comfortable. It really helps your life to be comfortable in your clothes and to pass by a mirror and see your reflection and to enjoy it.

GLENN: Was the first Savannah Band the same as it is today?

AUGUST: The very first Savannah Band, back in my college days, had Gichy Dan singing lead, Corey Daye singing background, and Shep Coppersmith, who was a dark fellow, singing lead. There wasn’t Mickey and there wasn’t Andy. Then Gichy Dan drifted away and became a Jehovah’s Witness. Then Stoney got this whole theory of being proud of the mulatto heritage. That theory came about in late 1974, and as a result, he started firing the dark people in the band. He lost the drummer and the singer, because he started spouting all these philosophies about how half breeds are better than white and better than black, because it’s a combination of both worlds. Then he got a mulatto drummer, Mickey, and he got rid of Shep and made Corey the lead singer. And he was searching for a piano player and we found Sugar Coated Andy—who was born in Tahiti of all places. That excited Stoney—a Tahitian Puerto Rican was definitely the last component of the Savannah Band. But Gichy Dan was originally in there singing lead till he went off on this religious crusade. I just produced him about a year ago. He’s got a hot tune, Laissez Faire.

GLENN: Did the Savannah Band ever play live?

AUGUST: The Savannah Band played live one week in Florida in 1978. We played the Limelight in Miami and we did a concert with the Village People at the J’ai Lai, and the University of Miami. Five gigs. Other than that we never played live after signing with RCA. We played live all the time before that, before Stoney embellished the sound with 16 horns and 30 strings. Which he doesn’t want to compromise with. If he goes on the road he feels he should have his horn section—at least.

GLENN: What are your favorite swing bands?

AUGUST: I don’t have many. I’m a student of Cab Calloway and his bands. And they really don’t get the credit they deserve. They never really surfaced as a band. I’m a student of Tommy Dorsey and Glenn Miller, the obvious ones. And obscure stuff where the material is more important to me than the bands. Things like one of my favorite tunes of all time, I Can’t Get Started With You, by Bunny Berrigan. Lena Horne is one of my favorite singers of that era.

GLENN: Savannah Band is one of the few modern bands to use a clarinet—why do you think clarinets aren’t used anymore? AUGUST: I would imagine the clarinet has disappeared in these terrible times because the clarinet is what one might call a timid instrument. For today’s dynamics, it is difficult for a clarinet to rise above the cacophony of guitars and such that have become the norm for today’s music. The clarinet is a wonderful instrument, in that it exudes and evokes such imagery. You can’t find a single other instrument that will do what the clarinet will do for the mind, in my opinion. In orchestration such as the Savannah Band uses, playing upon lush chords and vibes, it sums up the good and evil in the world— it’s like a combination of heaven and hell, the clarinet. Vibes, too, are “timid instruments,” so to speak, that have not been too dominant in today’s music. They can’t climb above the sound. In Stoney’s arrangements the clarinet is featured because it belongs there. The music is not abrasive, not cacophonous; it’s lush.

GLENN: Corey has a lush voice, too.

AUGUST: Yeah. As the critics say, “insouciant cooing.”

GLENN: So where does Kid Creole come in?

AUGUST: The Kid can be traced back as far as 1977. The Savannah Band went out to California in late ’77, to do the King Penett album and it was out there that we had our “internal problems.” As a result of the fact that Stoney was running the group much in the military fashion, he had put everyone into their own niches. I was to be the lieutenant, the right hand man, and I was to be the lyricist and the bass player. And only that. Obviously, I was growing as an artist, evolving into other things. I wanted to expand. I wanted to do music as well. I wanted to do more singing. But Stoney in his typical fashion said, “You are lyricist, you are bassplayer, that’s your niche. Corey, you are the singer.” Etc., etc… So it became a bit uncomfortable out in California. Though we had great times out there, it was a frustrating experience for me artistically. So that’s when I concocted this Kid Creole scheme, to be the other part of me: If there was to be August Darnell, and he was to be lyricist and bassplayer, background singer of the Savannah Band, then there was so much of me that needed further expression that there had to become another person. Gichy Dan came along, and I let some of my other talents escape into that. That was my first real production, outside the Savannah Band. It was a vehicle for getting out some of my tunes, some of my musical expression. But not yet the other side of me, the performer, the singer. So I had to devise a way to release that, and my mind flew back to King Creole, that wonderful film of Elvis Presley’s, and that was it. The term Creole came to mind because at that time, I was dating a Haitian girl who spoke Creole, a patois of French, and there was something about the language that was fascinating to me. It’s street French. A lot like street English. It’s what the Haitians speak when they’re not in school. Today, in fact, they’re teaching it in schools which is interesting. Much like they’re trying to teach slang today. They tell me they’ve added slang to the English curriculum. But I liked the language and I liked the flow of the word Creole. There’s something euphonious about it. So my mind went back to King Creole. Then on my lovely wife’s birthday, at Eddie Condon’s, my wife took a napkin and wrote on it, “Kid Creole” and that was the beginning.

MRS. DARNELL: And then came the Coconuts.

AUGUST: There was going to be an embellishment of sorts whereupon I wanted to display two Fay Wrays. The idea of Fay Wray, that poor innocent blonde child in the jungle has always been a fascinating idea. The original was so good in King Kong that I said, “I must put on pedestals two Fay Wray’s.” Thus, Kid Creole and the Coconuts. Now that I look back at it I can understand Stoney’s position, seeing that the Savannah Band was his brainchild. His mind is very militaristic. He likes to keep things in their place. As I say, I don’t begrudge Stoney his authoritarian quality. In the Kid Creole project I find that too much liberty is like too much love, it’s worse than none at all. When you allow people to give of themselves too much, they have a tendency to go overboard. We still manage to work together today very well. We have our arguments, of course, every other month, but there’s nothing wrong with that. We see eye to eye when we’re in the studio, and I still love the songs we come up with.

GLENN: Do you like producing?

AUGUST: Not really. I don’t see myself producing anyone else much anymore. I see myself producing Kid Creole or any of my other projects. It’s not one of my ambitions. I did it because there was something unique that needed to be expressed and that was a way of doing it. Things that really move me—like James White—I would always produce. Sugar Coated is putting out his own album, Coated Mundi.

GLENN: Are you producing?

AUGUST: Co-producing. We’re working hand in hand. He’s quite capable of producing himself.

GLENN: He did a good job with Don Armando’s Second Avenue Rhythm Band.

AUGUST: Andy is a great arranger and a wonderful musician.

GLENN: What are your ambitions?

AUGUST: I want to perform. But more than that I want to get these screenplays and plays of mine into the files; I want to stage them. I want to finally take them out of swaddling clothes and put them in the limelight.

GLENN: Are you a believer in UFOs?

AUGUST: To me the existence of other bodies and other worlds is as real as the existence of myself.

GLENN: Are you psychic?

AUGUST: I don’t believe I am. I am, however, a believer in fate. Fate above and beyond free will. I don’t think we are masters of our fate. I think that we are controlled by a force greater than us. There’s a large book somewhere and it has all our lives mapped out. What we’re going to do, when we’re going to die, and when we’re going to be born again. It may not be written in English, but it’s written.

GLENN: What are your favorite chords?

AUGUST: Without a doubt the D flat seventh flat minor. I’ve used it in almost every song I’ve ever written. My second favorite chord is C eleventh. The D flat seventh flat minor is a dark chord. It makes you think of all the melancholy nocturnal interludes.

GLENN: Do you have a vivid dream life?

AUGUST: Yes, my dream life is so vivid that I feel twice as old as I am. I have lived two days per dream since I was 9-years-old. Usually, they’re in black and white, but they’re very, very intense situations, very dramatic. I used to think that the events were merely echoes of things that happened in my life, or perhaps they were indications of things to come, but they never came. But I’ve been having an affair with the Netherlands in my dreams.